Crossing Runtimes: Accelerating C# with Rust and Cursor

How we optimized our core logic in a C# application using Rust

Introduction

Writing code that runs fast is a key component in many time-critical applications. A spaceship traveling to Mars must be right on the spot and cannot have any significant delay when calculating flying routes. The same applies to a project we’ve been working on – timing is critical, and our objective is to be fast enough that the user won’t even feel we are there.

In this article, we will share a cool experiment we conducted that proved extremely valuable for our project, with an average 6.5× improvement in the performance of a key hot path.

The problem

While working on a feature that involved file text-scanning, we identified a bottleneck in one of our key hot paths. On this hot path, we search for sensitive data in potentially long texts, and while doing so, the user cannot use the file containing that text. Since we do not want to degrade the experience for the end user, we had to find a very fast tool for text scanning.

Our application is mostly written in C#, and we were using its native library for regex matching to search for sensitive data. This library is considered to be well optimized, but unfortunately, it was not fast enough for our use case.

Initially, we tried to optimize our code that uses that library, but we didn’t find any fixes for our performance issue. Then, we searched for other libraries for regex matching, but we didn’t find any that were both suitable for our application and could solve our performance issue.

At this point, we had to be creative and look deeper into potential solutions outside the C# world. We previously heard that Rust, which we already use in other parts of our product, has a very good regex engine, and we wanted to test it out and see if it would solve our performance issues. To do so, we needed to use a Foreign Function Interface (FFI).

FFI in a nutshell

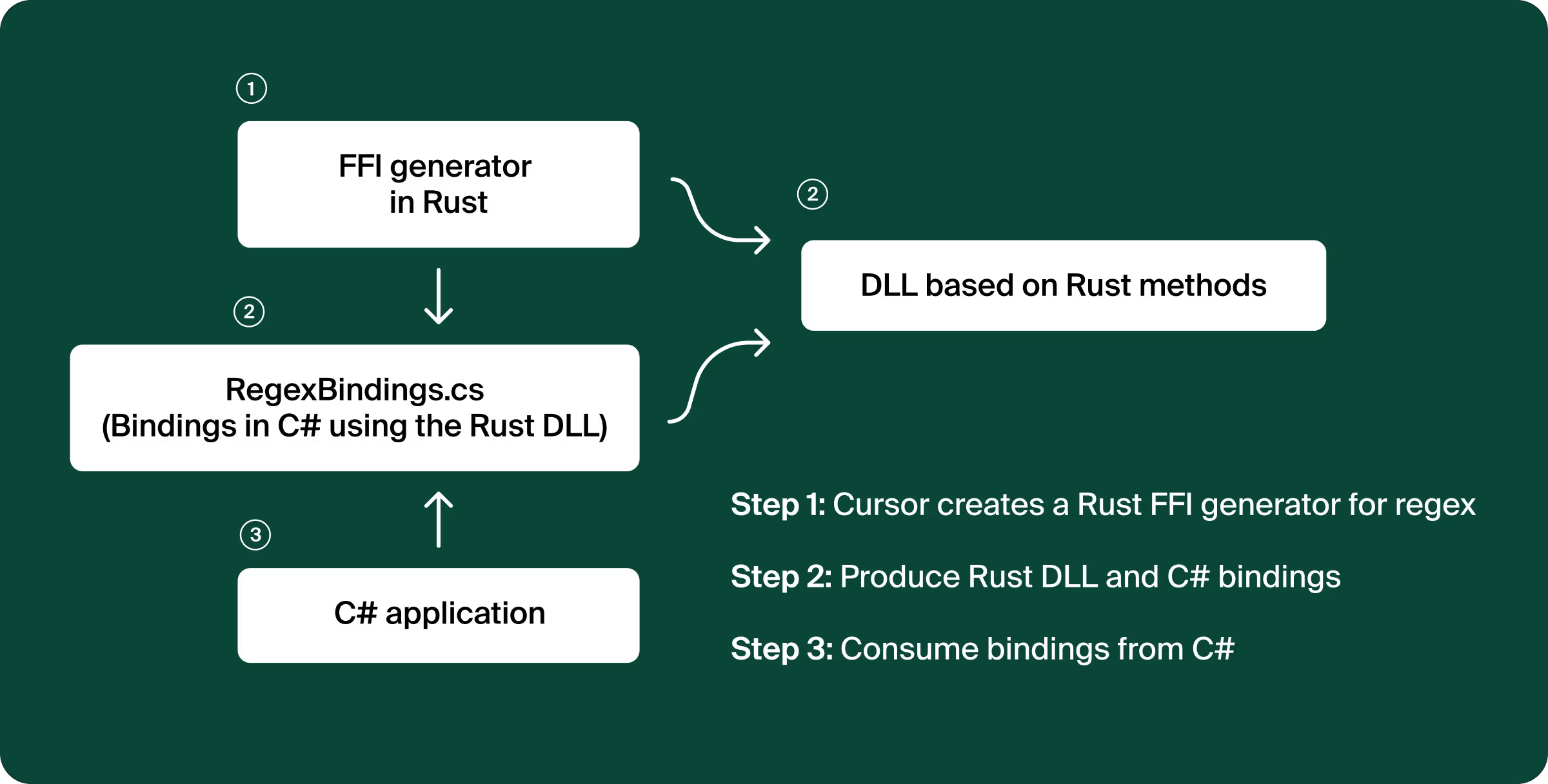

FFI is a mechanism that allows code written in one programming language to call into code written in another, crossing language and runtime boundaries while still feeling relatively native to the caller. In our case, FFI enables interoperability by compiling Rust code into a DLL that is loaded and invoked from managed code. A thin C# wrapper calls the DLL’s exported methods, transferring data across the managed–native boundary and returning results to the runtime, allowing performance-critical logic to run in Rust while the higher-level integration and API surface remain in C#.

How did it work out for us?

As mentioned, Rust has a strong and performant regex library, and we wanted to test it out for our use case. We leveraged Cursor to help us quickly create a performant Rust-based regex library for C#.

Our prompt for Cursor was to build a lean C# wrapper for the Rust regex library using an FFI framework. In no time, we had a fully functional C# library that uses Rust’s regex engine. Cursor leveraged an existing library for FFI called interoptopus, and used it to build the library.

Reviewing Cursor’s code, we see that it created a wrapper for Rust's regex library. In this wrapper, it marks methods using attributes for the FFI library to export them. In addition to the wrapper code, it generated Rust code that generates a C# class (this is a functionality of the FFI framework). That class is able to invoke the methods from the Rust DLL.

A nice side note – since we already had unit tests for our application, we got the UTs for the Rust library for free. This gave us lots of confidence in switching to the new library.

After Cursor completed generating code and creating a C# library, we took it out for a ride. It was cool to see that even though the library exposed methods that looked like any other C# library, the performance sure didn’t look like our C# baseline!

For our long text use case, the Rust library was able to improve running time by 3-10 times! And in most cases, it was around 6 times faster. This gain is critical for our application. However, we did come across cases where the C# implementation was much superior.

In the benchmark section that follows, we try to understand these cases empirically by comparing the C# regex library with our new Rust-based library, and collect some interesting and promising insights.

Benchmark

To test our Rust library, we designed a benchmark to evaluate performance. Our test criteria involved taking a set of patterns and keywords to identify matches within a given text. Rust has a functionality called RegexSet that does exactly that. In C#, we had to either:

- Match each pattern individually against the text

- Create a concatenated pattern with named groups to match against the text

Both RegexSet (Rust) and the concatenated method (C#) efficiently match an input against a large collection of regexes at once, returning which patterns matched without performing separate evaluations for each regex.

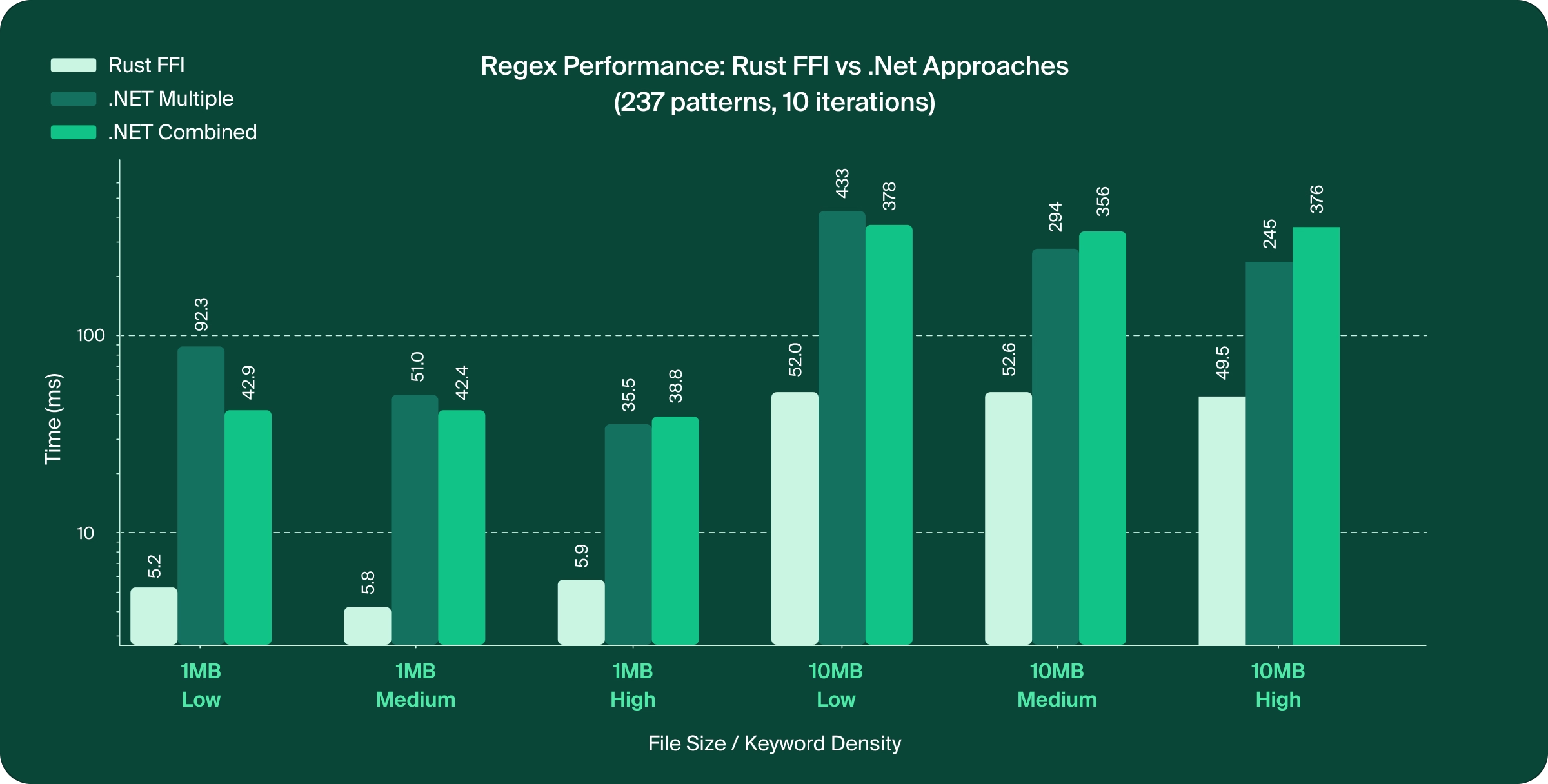

We generated a test suite with 237 different patterns. We tested across file sizes ranging from 1MB to 50MB, with varying match densities to simulate different real-world scenarios.

These benchmarks revealed how significant the gains were from using the FFI approach.

For small to medium files (1-10MB), the Rust FFI consistently delivered 4.9-8.25× performance improvements. The most impressive result came with 1MB files at low match density – 8.25× faster processing (5.2ms vs 42.9ms). Even in cases where the gains were less substantial (higher match density), we maintained a max 7.3× performance advantage. Here's what this looks like in practice (Y-axis is in log scale):

When we tested longer documents, we noticed that the performance degraded a bit, but the gains remained impressive. For a 25MB file, FFI was 4-7.2× faster, and for a 50MB file, FFI was 3.3-6.5× faster.

This shows that across many different test cases, the FFI approach was able to achieve superior results.

As promising as these results are, we did identify cases where the FFI wasn’t better than the C# approach. Complex patterns worked better in the FFI approach, while simple regexes or a few keywords worked better in the C# approach. The same goes for a regex with many alternations. On the other hand, when we included sophisticated patterns like email validation (\b[A-Za-z0-9._%+-]+@[A-Za-z0-9.-]+\.[A-Z|a-z]{2,}\b) and date of birth regexes (which include keyword alternations for month names), the FFI performance surpassed C#’s. Since these cases represent our main use case, we decided to adopt the Rust-based FFI implementation.

But how easy is it really?

Below, we provide a shortened example that shows how to create a library that supports the IsMatch method.

In the Rust project Cursor created, there are two main files – ffi.rs and lib.rs.

lib.rs

lib.rs is the library's entry point, which automatically generates C# bindings from the Rust FFI functions. This code is very specific to interoptopus (the FFI framework), thus we omit it from this blog.

ffi.rs

In this file, we declare functions, data types, and error handling that are marked in a way that exports those to the C# code and lets it use them. See the [ffi_type] attribute.

use interoptopus::{ffi_function, ffi_type, patterns::string::AsciiPointer};

use regex::Regex;

/// Error codes for regex operations

#[ffi_type]

#[repr(C)]

pub enum MatchResult {

Match,

InvalidPattern,

InvalidInput,

NoMatch,

}

/// Check if a regex pattern matches the input text

#[ffi_function]

pub extern "C" fn regex_is_match(pattern: AsciiPointer, text: AsciiPointer) -> MatchResult {

// Convert C strings to Rust strings

let pattern_str = match pattern.as_str() {

Ok(s) => s,

Err(_) => return MatchResult::InvalidPattern,

};

let text_str = match text.as_str() {

Ok(s) => s,

Err(_) => return MatchResult::InvalidInput,

};

// Compile and execute the regex

match Regex::new(pattern_str) {

Ok(regex) => {

let is_match = regex.is_match(text_str);

if is_match {

MatchResult::Match

} else {

MatchResult::NoMatch

}

}

Err(_) => MatchResult::InvalidPattern,

}

}

/// Export the inventory of FFI functions for binding generation

pub fn inventory() -> interoptopus::Inventory {

use interoptopus::{InventoryBuilder, function};

InventoryBuilder::new()

.register(function!(regex_is_match))

.inventory()

}Conclusion

FFI can be an amazing tool to harness the performance advantages of other languages, letting you combine the productivity of C# with the speed of Rust. In our case, it enabled a critical regex hot path to run around 6× faster. Tools like Cursor make this integration surprisingly approachable, generating the necessary bindings and boilerplate so you can focus on the results.

Credits

I would like to thank Michael Maltsev for his guidance and mentoring on Rust and FFI.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)